Introduction

Hypothyroidism is a condition caused by the underfunction of the thyroid gland, which is essential for producing hormones that regulate our metabolism. In other words, hypothyroidism happens when the thyroid doesn’t produce enough thyroid hormones.

Subclinical hypothyroidism, the subject of this article, represents a mild form of hypothyroidism. It typically does not show symptoms but can be identified through laboratory tests.

Normal Thyroid Function

Located at the base of the neck, the thyroid gland is a vital organ responsible for generating hormones that dictate the pace of our metabolism. These hormones are known as triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). An increased level of these hormones in the blood speeds up the metabolism, whereas a decrease slows it down.

Hypothyroidism results from insufficient T3 and T4, whereas hyperthyroidism is due to their excess.

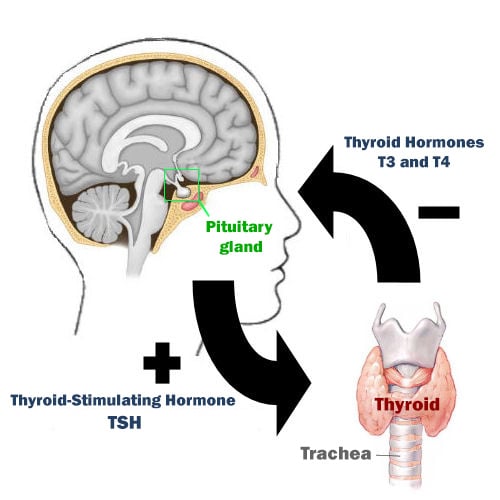

The thyroid’s production of T3 and T4 is regulated by another hormone, called Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH), produced in the brain’s pituitary gland.

In simple terms, when the body needs to boost its metabolism, the brain ramps up TSH production, which in turn prompts the thyroid to produce more T3 and T4.

Conversely, when the body needs to decelerate metabolism, TSH production drops, leading to reduced T3 and T4 output by the thyroid gland.

The release of TSH is carefully controlled to ensure the thyroid produces just the right amount of T3 and T4, avoiding any excess or shortage of these hormones.

More than 99% of the T4 and T3 circulating in the bloodstream are bound to a protein called TBG (thyroxine-binding globulin).

These TBG-bound hormones are innocuous and cannot be used by organs and tissues. Therefore, only a tiny fraction, called free T4, is chemically active and can modulate the body’s metabolism.

What Is Subclinical Hypothyroidism?

In classic hypothyroidism, patients typically have low levels of T3 and T4 and elevated levels of TSH. This occurs because they have a diseased thyroid gland that is unable to produce more hormones, even when stimulated by high levels of TSH. As much as the pituitary gland increases the release of TSH, the thyroid cannot respond to this hormone stimulus.

For many patients, the thyroid malfunction starts off mildly and gets progressively worse, requiring the pituitary gland to secrete increasingly higher levels of TSH over time to maintain proper thyroid function.

The disease progresses to a point where the gland is so impaired that it can no longer produce minimal amounts of hormones, even when stimulated by very high levels of TSH. When this happens, the patient no longer has subclinical hypothyroidism, but rather overt hypothyroidism.

Subclinical hypothyroidism is a kind of “pre-hypothyroidism,” a phase preceding the onset of clinical hypothyroidism.

In the subclinical phase, the thyroid, while not functioning at its best, can still produce thyroid hormones when stimulated by elevated levels of TSH. Consequently, the patient exhibits higher-than-normal TSH levels, yet maintains normal T4 and T3 levels. This absence of significant T4 and T3 imbalance typically results in a lack of noticeable symptoms during this phase.

About 5 to 10% of the population has subclinical hypothyroidism, and a large part of them are unaware of this condition.

Subclinical hypothyroidism is more prevalent in women than in men and occurs more commonly in Caucasians and older adults. The causes are similar to those of overt hypothyroidism, with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis being the most common.

Diagnosis

Subclinical hypothyroidism is identified through laboratory testing. Patients with this condition typically maintain normal thyroid hormone levels (T3 and T4), leading to few, if any, noticeable symptoms.

Patients with subclinical hypothyroidism usually have normal free T4 levels and elevated TSH levels, often ranging between 5 and 10 mU/L.

When TSH levels exceed 10 mU/L, it frequently indicates a transition from subclinical to overt hypothyroidism, characterized by lower free T4 levels and more apparent hypothyroid symptoms. In subclinical hypothyroidism, elevated TSH levels are common, but they rarely rise significantly above 10 or 15 mU/L.

Symptoms

To be classified as subclinical hypothyroidism, patients typically should not exhibit apparent symptoms of hypothyroidism.

In such cases, while free T4 levels remain within the normal range, patients might experience only mild and vague symptoms, like slight fatigue, diminished motivation for tasks, or a mild cold intolerance.

These symptoms are not unique to the condition and can be experienced by anyone, often during times of stress, heavy workload, or at the beginning of viral illnesses.

Hence, the absence of pronounced clinical symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism means that its diagnosis relies solely on laboratory testing.

Progression from Subclinical to Overt Hypothyroidism

A significant number of individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism eventually progress to overt hypothyroidism. Research indicates that within 10 to 20 years, as many as 55% of those with subclinical hypothyroidism evolve into the full-fledged disease.

The likelihood of this progression is linked to the initial levels of TSH; notably, patients with TSH levels in the range of 12 to 15 mU/L face a higher risk. Additionally, thyroid antibodies, such as anti-TPO, are a significant factor.

The underlying disease also greatly influences the risk of evolving into clinical hypothyroidism. Those suffering from autoimmune thyroid disorders, like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, or who have undergone intensive treatments like radioiodine therapy or high-dose radiation, are more susceptible to developing overt hypothyroidism.

Interestingly, some cases of spontaneous recovery in subclinical hypothyroidism have been observed, although the exact frequency of such occurrences remains somewhat unclear.

It has been noted that certain individuals meeting the criteria for subclinical hypothyroidism eventually show normal test results, despite not undergoing any specific treatment. This is typically seen in patients with consistently lower TSH levels, under 10 mU/L, and who test negative for thyroid antibodies.

Many individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism experience no apparent symptoms, leading to a scenario where they may unknowingly develop the condition and, over time, also recover from it without ever being aware. This lack of awareness means such cases often go unrecorded, posing a challenge in accurately determining how frequently spontaneous recovery occurs in subclinical hypothyroidism.

Implications

Despite typically being symptomless and sometimes resolving spontaneously, subclinical hypothyroidism doesn’t seem to be a completely harmless problem.

Several studies suggest an association between subclinical hypothyroidism and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, such as angina pectoris and heart attack, especially in patients with a TSH greater than 10 mU/L.

Patients with subclinical hypothyroidism also tend to have higher cholesterol levels than the general population.

Besides cardiovascular concerns, there’s an elevated risk of hepatic steatosis, particularly in those with higher TSH levels, adding another layer of potential health complications associated with subclinical hypothyroidism.

Treatment

One of the primary dilemmas when diagnosing subclinical hypothyroidism is deciding whether to initiate treatment with levothyroxine, the synthetic form of the T4 hormone.

So far, no significant benefits have been shown from using levothyroxine in asymptomatic patients with TSH levels between 4.5 and 10 mU/L, making its treatment in these cases a subject of debate.

Those in favor of levothyroxine use argue that there is no evidence of harm from hormone replacement, and it may improve symptoms like fatigue and mild mood changes, which might have gone unrecognized.

Currently, the consensus recommends monitoring TSH levels every 6 to 12 months for these patients, except when they exhibit symptoms clearly attributable to hypothyroidism.

However, in certain situations, the choice to forego treatment isn’t straightforward. This includes patients with high cholesterol, an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, or positive thyroid antibodies.

Recent research suggests that treating subclinical hypothyroidism in adults under 65 could reduce cardiovascular event-related mortality, a benefit not observed in older patients. Consequently, many physicians now recommend levothyroxine for younger adults with TSH levels above 7.0 mU/L.

Treatment with levothyroxine might also boost fertility in women struggling to conceive.

For patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and TSH above 10 mU/L, there’s less controversy. Most international endocrinology societies advocate using levothyroxine in these cases, as it helps prevent the progression to overt hypothyroidism.

In summary, treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism is generally advised in the following cases:

- TSH above 10 mU/L.*

- Women facing difficulties in conceiving.

- High anti-TPO antibody titers.

- Clear symptoms of hypothyroidism (new or worsening fatigue, constipation, cold intolerance) or an enlarged goiter.

* Owing to cardiovascular risks, an increasing number of endocrinologists begin treatment in patients under 65 with TSH higher than 7.0 mU/L.

The levothyroxine dosage should be the lowest possible that maintains TSH between 0.5 and 2.5 mU/L in younger patients and 3 to 5 mU/L in older patients.

The prescribed dose of levothyroxine must be carefully titrated to maintain TSH within a target range of 0.5 to 2.5 mU/L in younger patients and 3 to 5 mU/L in older patients, ensuring that the lowest effective dose is used for optimal treatment.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism During Pregnancy

The thyroid hormone physiology in pregnancy undergoes significant changes, resulting in different standard TSH levels for pregnant women.

In the first trimester, subclinical hypothyroidism is identified when normal free T4 levels are accompanied by a TSH level above 2.5 mU/L. For the second and third trimesters, subclinical hypothyroidism is indicated by TSH levels exceeding 3 mU/L.

Considering the vital importance of thyroid hormones for the neurological development of the fetus, the prevailing medical consensus advocates for the treatment of all pregnant women who fit the criteria for subclinical hypothyroidism.

References

- Subclinical Hypothyroidism – JAMA.

- Guidelines for the Treatment of Hypothyroidism – American Thyroid Association.

- Subclinical Hypothyroidism: Deciding When to Treat – American Family Physician.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism in nonpregnant adults – UpToDate.

- Subclinical Hypothyroidism: An Update for Primary Care Physicians – Mayo Clinic proceedings.

Author(s)

Pedro Pinheiro holds a medical degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and is a specialist in Internal Medicine and Nephrology, certified by the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) and the Brazilian Society of Nephrology (SBN). He is currently based in Lisbon, Portugal, with his credentials recognized by the University of Porto and the Portuguese Nephrology Specialty College.

Leave a Comment